In a quiet corner of Greenfield, a 2010 construction project unexpectedly broke ground on an urban time capsule: five concrete skateboarding bowls dug into the earth, filled with rubble yet remarkably intact.

The contractors had unknowingly exposed the remnants of the Turf, a popular skate park from the 1980s and ’90s.

When news of this discovery broke, skateboarders in this southwest suburb of Milwaukee, who once rode this park, emerged from the woodwork in packs, shovels in hand, eager to relive their fondest memories. By nightfall, the crew had completely dug out one of the smaller bowls, and a few were even able to skate it.

It would be a long road ahead, but more than a decade later, the city of Greenfield has successfully preserved this piece of urban archaeology that fueled a generation of skateboarders. By blending historical elements with modern skate park features, the reconstruction not only offers a nostalgic return to roots but signifies a forward-thinking change for the future of skateboarding culture.

“ In the ’80s, the Turf was a destination skateboard park. It brought skateboarders from all over the world, let alone the U.S. If you were a pro in the 1980s, you came to Milwaukee and you skated the Turf . “

The Turf Skatepark, originally named the Surf-N-Turf, opened in 1979 during a skateboarding boom. In its heyday, the Turf resembled what you might expect from an ’80s skate park — brightly colored carpet, flashing pinball machines and arcade games, and a jukebox that played punk rock records over the loudspeakers.

Jesse Geboy remembers the first time he set foot in the Turf as a young teenager in the early 1990s. The controlled chaos and dimly lit room was equally intimidating as it was inspiring.

“It was mind-blowing to me that to see there was actually a place designated for skateboarding when I was pretty much isolated to my driveway with my own homemade ramps or skating illegally in the street,” Geboy says.

The park’s shining feature was its five concrete swimming pool-like bowls. Unlike many other skate parks, the Turf’s bowls were housed inside a building, which allowed for year-round skating. Each bowl was unique with different shapes, sizes and names alongside whatever gnarly reputation it had earned. They were affectionately known as the Lip Slide Gully, the Footie Bowl, the Clover (or the Triple Pool), the Key Hole Pool and the Half Pipe Capsule.

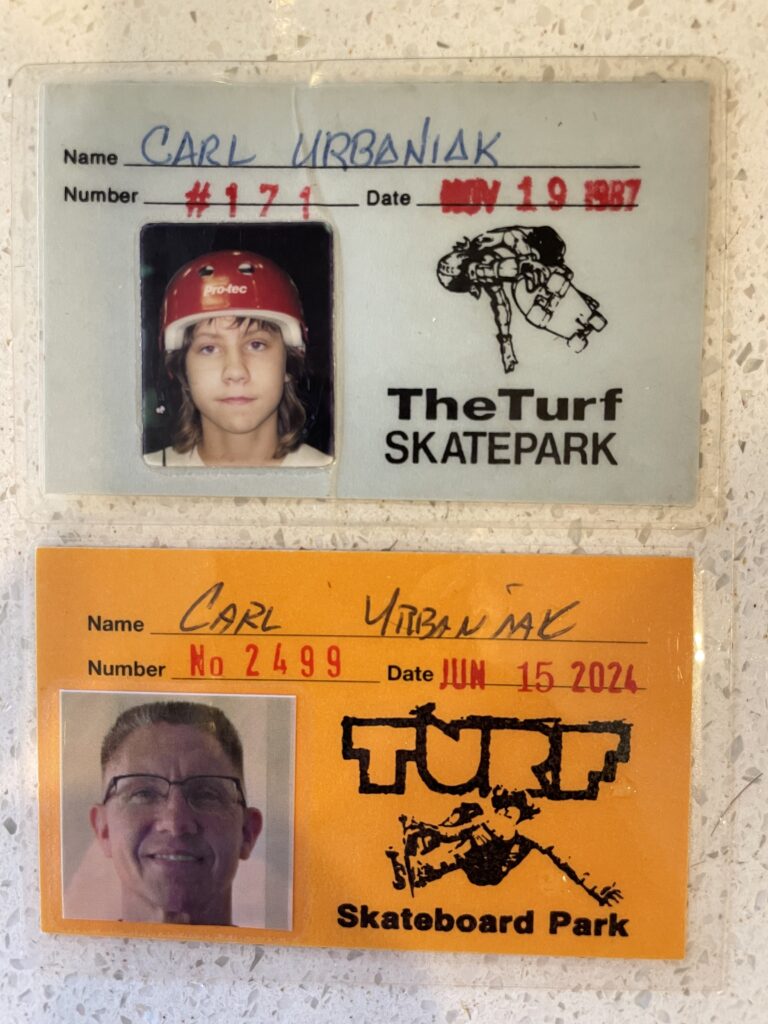

The Turf quickly became a midwest hub for skaters and gained national notoriety in the skateboarding community. Tony Hawk is just one household name who found himself 15 minutes outside Milwaukee to check out the spot. Carl Urbaniak, a Turf skate park regular in the ’80s and ’90s, recalls how the park influenced Milwaukee’s skateboarding culture at the time.

“In the ’80s, the Turf was a destination skateboard park. It brought skateboarders from all over the world, let alone the U.S. If you were a pro in the 1980s, you came to Milwaukee and you skated the Turf,” Urbaniak says.

The Turf was beloved by many, but times and trends inevitably evolved. The park closed in 1996 partly due to the rise in popularity of street-style skating. The owners filled the bowls with gravel, and it was buried beneath Wisconsin dirt. The building that enclosed the bowls served as a cabinet company and a lawn and garden shop for the next few years.

Photo by: Carl Urbaniak

After several last-ditch efforts to save the Turf fell flat, the community reluctantly accepted its fate. Geboy recalls driving down Loomis Road past the abandoned site after it closed.

“You knew what was underneath that floor,” Geboy says. “It was just one of those things that was always painful to know that it was there and that you were never to see it again.”

This grim reality persisted until 14 years later, when the Wisconsin Department of Transportation began a construction project for a new highway off-ramp, exposing the corner of one of the bowls. This uncovering reignited the community’s love for the Turf and sparked a desire to reconnect with their younger selves.

The discovery was quickly brought to the attention of Greenfield mayor, Mike Neitzke, who says the restoration of the Turf has been one of the most significant things to happen to the city of Greenfield in his almost 20 years as mayor.

“There’s a flurry of things that generate public interest and contact with the mayor’s office,” Neitze says. “Of everything, even after that time to present, nothing generated as many contacts with my office.”

These contacts came not only from Wisconsin, but across the country and around the world. Neitzke recalls receiving phone calls and emails from people who remembered the Turf — whether they lived in Greenfield as a kid and had moved elsewhere or had visited the park once for an adventure.

It quickly became clear to him that the Turf needed to be revived.

Moreover, Neitzke felt it was important to pursue this project because of its historical significance.

“It’s sort of like the Lambeau Field of skateboard parks. The more you dig into it, there’s only one of these in the world. The kind of history that it had, all the other types of bowls that were like this have long since gone away,” Neitzke says. “So we feel really, really lucky to have this historical presence in the city. And it needed to be preserved.”

The state Department of Transportation eventually agreed to sell the two-acre parcel back to the city under the condition that it would be used as a free park. After much persistence and patience, the city purchased the property from the department in 2019 for just $1, which Neitzke paid himself.

“ It’s not just a skateboard park. It’s kind of a place where you mature, and you hone your skills, and you commit to something that makes you ultimately a better human being. “

With the unique opportunity — and what many would call a significant responsibility — to restore a park from an earlier era of skateboarding, the city wanted to make sure the project was done well to ensure the park’s longevity. The city partnered with Grindline, a renowned skate park construction company based in Seattle, to design and build a new Turf skate park.

Skate styles have changed in some ways since the ’80s, and the city wanted to appeal to the current skate scene while preserving the park’s historic aspects. To blend the old with the new, the plan included reconstructing the five existing bowls, adding a sixth bowl and creating a substantial street-style course. Elaborate efforts were made to ensure the bowls were recreated in their original locations with nearly identical dimensions.

The sixth bowl was created in collaboration with Grindline and local pro skater, Sam Hintz, with the intention to be more modern while still having parallel features to the original bowls. The park will be unique as it combines older skate park features with more modern obstacles, according to Jeff Katz, Greenfield’s director of neighborhood services.

“I think people really enjoy the history, the fact that they’ll be able to skate something that was historic and designed as skate parks were back then, along with all the new skate park features we’re creating that you would see in any modern skate park,” Katz says.

The skateboarding scene has shifted since its first emergence in the ’70s. Back then skateboarding was heavily associated with counterculture and was simply less popular. Modern skateboarding has evolved significantly.

“It’s been a lot more commercialized, but with that, it’s been a lot more widely accepted,” Geboy says, reflecting on how the sport has changed from when he was a kid to now. “It was always illegal in the streets and at private businesses, but now we have the luxury of having public skate parks, and The Turf being one of those is even more incredible.”

In 2020, skateboarding became an Olympic sport and its legitimacy as an extreme sport gained greater public visibility and acceptance. Despite these shifts, much of skateboarding remains timeless.

Both Geboy and Urbaniak noted that the values deeply rooted in skateboarding culture remained unchanged. At the skate park, age, gender or skill level doesn’t matter. What truly connects people is a shared passion for skateboarding and a strong sense of respect and mentorship. Neitzke, though not a skateboarder himself, recognizes how special the skateboarding community is.

“It’s not just a skateboard park. It’s kind of a place where you mature, and you hone your skills, and you commit to something that makes you ultimately a better human being,” Neitzke says.

The Turf is projected to attract skateboarders from all over the country to experience a nostalgic glimpse of the ’80s skate scene. Looking forward, the city hopes to have part of the park open before winter and the entire park completed by spring 2025.

There’s an old saying in skateboarding coined by skateboarding legend Jay Adams: “You didn’t quit skateboarding because you got old, you got old because you quit skateboarding.”

Both Urbaniak and Geboy are set on not getting old. When the park opens, they’ll be there with their families and skateboards in hand, ready to relive the thrill of those bowls once more.

“It’s been really cool to follow this whole experience . Having been a kid and seen it, to it being gone and buried for years, and then to see it exposed now in the natural light,” Geboy says. “It’s totally a dream come true and something I never thought would happen again.”

Cover photo: Jesse Geboy skates the Half Pipe Capsule for the first time since the mid ‘90s. Photo by Lauren Aguila.

Tile photo: Jesse Geboy skates effortlessly across the new street-style course at the construction site of the Turf Skatepark. Photo by Lauren Aguila.

Published on Dec. 9, 2024