Walking into Gee’s Clippers, it’s not surprising the space is built for more than haircuts.

Atop a replica of the Milwaukee Bucks’ Fiserv Forum court flooring, 72 chairs from the Milwaukee Exposition, Convention Center and Arena, also known as the MECCA, and the BMO Harris Bradley Center split the room’s waiting area. A steel vault door stands at the end of the court — a remnant of the building’s original structure as a 1930s savings bank — and ceiling trim outlines the room’s nearly 25-foot ceilings like icing on a wedding cake.

In the shop’s vending machine, travel-sized Mane ‘n Tail shampoo bottles and 360 Style Wave Control Pomade fill slots you’d expect to be packed with chocolate bars or soda.

Tucked behind the vault’s entrance is a new addition to the historic Black barbershop: Gee’s MKE Wellness Clinic, a weekly service open to all intended to address health disparities in Milwaukee’s Black community.

“For Black guys, a barber is definitely a trusted individual,” says founder Gaulien Smith. “Most times a guy is not going to go to a barber to get his haircut if he doesn’t really trust him. … It’s a very intimate type of relationship.”

Turning a trusted neighborhood institution — the local barbershop — into a trusted source of health and wellness information is helping Milwaukee’s north side community bridge the divide between health and social services in communities of color. Black people in Wisconsin have some of the poorest health outcomes, and Smith’s shop blends community with awareness to change the futures of customers while also addressing long-standing inequities.

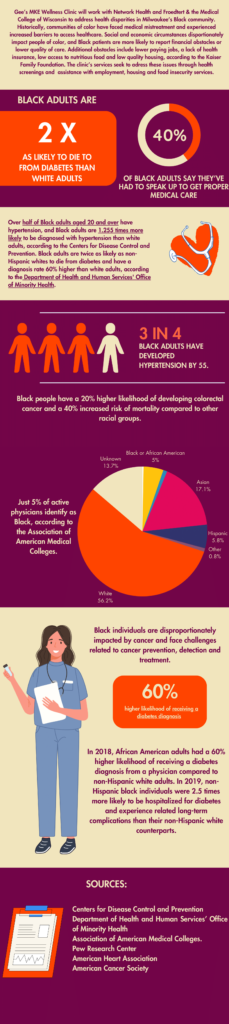

Working in partnership with Network Health and Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, the clinic currently offers services including blood pressure checks, glucose monitoring, flu shots and screenings for body mass index. The clinic has also offered COVID-19 vaccines and screenings for cholesterol, memory, hearing, vision, cardiovascular issues, HIV and sexually transmitted diseases, as well as assistance with employment, housing, food insecurity and GED completion, Smith says. The clinic’s team plans to offer these services again starting in the summer of 2024.

Currently open every Friday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., their future goal is to provide services three to four days a week, says Jasmine Johnikin, the clinic’s main coordinator.

Smith became passionate about early illness detection after his father died at age 62 following a stage 4 colon cancer diagnosis. At the time of his father’s death in 2006, he didn’t think he would later have a clinic at the shop.

A friend, Wendy Collins, working for a health insurance company gave him the idea. The clinic opened in 2020 and has since served more than 2,000 patients. The clinic relaunched at the end of September after its partnership with Network Health and Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin started at the end of June.

Johnikin, a community outreach nurse with Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, says it’s important for clients to see someone who looks like them. Just 5% of physicians identify as Black, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Her main concerns in the community are high blood pressure and diabetes. More than half of Black adults ages 20 and over have hypertension, and Black people are 1.255 times more likely to be diagnosed with hypertension than white adults, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Black adults are twice as likely as non-Hispanic whites to die from diabetes and have a diagnosis rate 60% higher than white adults, according to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health.

“We’ve lost so much trust in the medical field in general, because there’s not a lot of us that look like us,” Johnikin says. “My biggest goal is to help people not be so scared.”

Johnikin hopes to create a safe space for community members to meet people where they are, detect preventable diseases early on and fill in the gap for health disparities, she says.

Network Health’s Chief Medical Officer Mushir Hassan says conversations about the partnership started in March between Smith and CEO of Network Health Coreen Dicus-Johnson.

Hassan says Smith brings a “secret sauce” by connecting marginalized communities to health care access through the trust he’s built with his clientele.

“Folks can feel comfortable and have trust in what he’s been doing, so being able to partner with someone like him who’s got that trust in the community allows us to be able to be seen as a trusted adviser when it comes to delivering health care information,” Hassan says.

The 8,000-square-foot shop stands at 2200 N. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in the heart of Bronzeville, the historic core of Milwaukee’s north side Black community. Jazz clubs in Bronzeville once hosted Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday. The shop originally opened in 1995 on Fond du Lac Avenue and Sherman Boulevard but moved to its current location in 2017.

“It’s the Vatican of barbershops,” says Antonio Perkins, who has worked at Gee’s for three years.

Perkins, who goes by Tone, says the systemic medical mistreatment Black people have experienced –– such as in the Tuskegee study, in which Black men weren’t treated for syphilis, or the case of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells have been used for medical research for decades without her family’s consent. That means “a lot of Black people are not very comfortable with going and getting health care from doctors.”

This systemic medical mistreatment contributes to a lack of trust, Perkins says.

“Black people have had very negative experiences in the health care field, whether it’s been being tampered with, or poorly treated, or even tortured and things of that nature.… We grew up listening to these stories,” Perkins says, adding that bringing a wellness clinic to the space is “the dopest combination that a barbershop could ever have.”

The shelves lining Smith’s office at the shop hold a 26.2 sign in reference to his marathon training — he’s run five in as many years and is running the Tokyo Marathon next March — and a Kentucky Wildcats baseball hat signed by the Miami Heat’s Tyler Herro, whose hair Smith has cut since Herro’s freshman year of high school.

He’s cut the hair of more than 200 NBA players, including Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O’Neal, Reggie Miller and Ray Allen. But he still recalls the neighborhood clientele he had out of his parents’ north side house, where he started to cut hair at 12 years old.

“[Milwaukee] has always been a blue-collar town,” Smith says. “This is where cars were made, where beer was brewed, where cheese was manufactured. To see now, we’ve been on a national stage as we are, it speaks volumes.”

Part of that pride extends to the success of the Milwaukee Bucks. As he uses a trimmer to shave the lining of a client’s beard, the conversation naturally turns to Giannis Antetokounmpo, who Smith says has “that winning DNA,” and the Bucks’ recent acquisition of Damian Lillard.

“You gotta understand. I’m 52 years old. We hadn’t won the championship since I was a year old. So, I mean, that was really, really huge,” says Smith, who is a season ticket holder, about the Bucks’ 2021 championship win. The black and white referee-striped shirt he is wearing is one of 60 provided by the shop’s partnership with the Milwaukee Brewers.

To get a sense of Milwaukee’s sports heritage, one only has to look at the shop’s court-inspired design. Fourteen jerseys from players like Damon Jones, George Koonce and Ray Allen — who got his hair cut at Gee’s for his entire tenure on the Bucks — are framed. Felt pennants, basketball hoops and signed vintage memorabilia fill the shop, and a flag split into sections corresponding to the Green Bay Packers, Bucks, Brewers and Wisconsin Badgers hangs from the northern wall.

Smith says it takes community members born and raised in Milwaukee to “change the narrative” of the city.

However, that effort extends beyond a wellness clinic. In 2016, it became the first barbershop in the country to charter a Boy Scout troop, Smith says. Ahead of the 2020 presidential election, the shop offered free haircuts to people who registered to vote there, and this June, it hosted an event to foster dialogue between Milwaukee police and youth residents.

Smith “lives, eats and breathes community,” Johnikin says. “He comes as his full self. He really has a heart and passion for servicing others in the community.”

Curtis Jones, a client of Gee’s Clippers for 23 years and a retired U.S. Postal Service mail carrier, says Smith’s advocacy for early detection of disease is the reason he found out he had late-stage prostate cancer.

During a haircut in 2020, Jones told Smith that his annual physical showed high levels of the prostate-specific antigen in his bloodstream. After the haircut, he agreed to get a cancer screening, which showed he would need immediate treatment.

“The expression on his face totally changed, ‘Man, what’s wrong with you, you know that can kill you,’” Jones says. “I owe it to him. He won’t take the credit. But if it wasn’t for him, I don’t know where I would be.”

Twenty-eight rounds of radiation later, Jones is in remission. He called Smith a “visionary” and says his commitment to the clinic is “a blessing” that has broken down barriers for Black men seeking health services.

Part of what makes the wellness clinic successful is that Smith’s staff stands behind its message of community. Gee’s barber Ceree Huley, a recovered addict following 27 years of struggle with substances, has used his role as a barber to mentor the clients that sit in his chair. A 1999 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel front-page feature about his journey, peppered with dots from thumbtack wear, is hung next to the price list on his wall.

Like many others in the community, Huley has experienced the personal impact of health disparities; his brother Gerald passed away from diabetes. Every Friday, he goes to the wellness clinic to get his blood pressure checked.

“The barbershop is the hub. I got a captive audience when you’re in my chair and I’m cutting your hair,” Huley says. “The barber is the one who is the encyclopedia — the person who knows all the happenings of the community and has a lot of experience that he loves to share with his audience.”

Smith echoed the sentiment, saying, “We don’t [always] talk about hair.” Instead, the conversation might turn to businesses, religion, kids and relationships.

And, of course, the Milwaukee Bucks.