On Wisconsin’s eastern border churns Lake Michigan, a powerful force of nature often compared to an ocean. Swimming in this great body of water can be intimidating, especially when faced with currents.

All currents form due to a variety of factors: wind, waves, sand formation, water temperature and more. Unlike the tides of the ocean — controlled by the gravitational pull of the moon — lake currents are almost entirely unpredictable. For many people, encountering currents can be a terrifying experience.

According to Michigan Sea Grant, an organization that funds research regarding use and conservation of the Great Lakes, people are most likely to come across one of five currents: rip, outlet, longshore, channel and structural. Here are Curb’s best tips on how to spot different currents — and how to escape them.

Rip currents

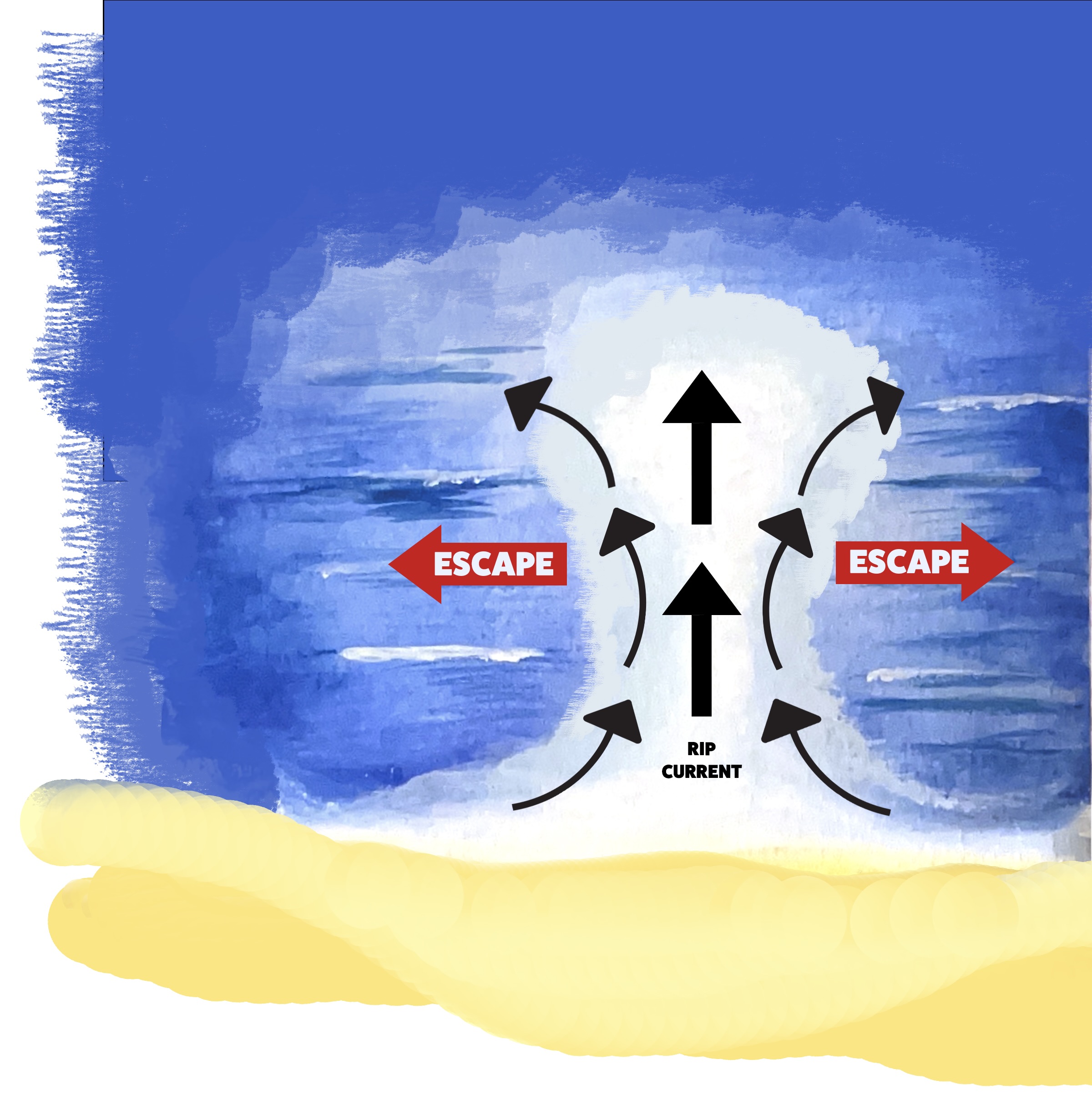

When a sandbar forms near a shoreline, crashing waves trap water between the sandbar and the shore. This trapped water flows back into the lake in the form of a rip current, also known as a “riptide.” This narrow but intense current has the power to suck someone deeper into open water. But don’t fret!

When encountering a rip current, the number one rule is to not panic. Take deep breaths, and don’t swim directly back to shore. Instead, swim parallel to the shoreline. Within a few strokes, you will be out of the rip current. Once you feel you are far enough away from the rip, you are safe to swim directly back to shore.

Outlet currents

Outlet currents form where areas of the Great Lakes are connected to rivers and streams. As water flows into the lake from these rivers and streams, the surge can be quick and powerful.

Here, you can apply your knowledge of rip currents and swim sideways, away from the outlet of water and back to shore. That said, Michigan Sea Grant recommends that people stay away from swimming in or near water outlets entirely.

Longshore currents

Have you ever gone swimming and realized you’ve drifted far from your spot on the beach? That’s because you’re encountering a longshore current.

These currents move parallel to the shore and can pull swimmers farther down the beach. Usually situated between two sandbars, longshore currents are mostly harmless but can become dangerous quickly when combined with other currents or structures.

Unlike rip currents, the best way to escape a longshore current is to swim directly to shore.

Channel currents

When encountering an island or structure — like a rock formation — near shore, look out for channel currents. These currents act like a river running parallel to the shore, with the most dangerous point being the area near the sandbar.

The best way to escape a channel current is to swim back toward shore and away from the sandbar.

Structural currents

Unlike other currents, structural currents are easy to predict and point out — but they’re responsible for more than 50% of current-related incidents.

Nestled alongside a structure in the lake, like a pier, these currents pull swimmers along the structure and into deeper water. Coupled with other types of currents, structural currents can act like a washing machine, moving swimmers to dangerous areas of the lake.

Swim in areas away from any pier to avoid these types of currents.

Feature photo: A sign warns swimmers and surfers of the danger of currents. Photo by Sophie Wooldridge