Off a paved road about 40 minutes northwest of Madison, just past the local apple orchard on Hall Road, there’s a tract of farmland the Nelson family has farmed since 1894.

In the 1950s, it was a dairy farm with one main barn. A decade later, the Nelsons added three large silos, built new outdoor shelters and raised cattle. Grain farming became commonplace by the 1980s when expansion began, reaching 2,000 acres at its peak.

Today, the Nelson farm in Poynette sits at about 1,400 acres, and the family has selected its next main crop: solar energy. It’s just the family’s latest evolution over the last 129 years to keep the farm in the family.

As family farms shrink, solar skeptics grow and the effects of climate change emerge, fourth-generation farmer Larry Nelson decided it’s time to switch to solar, promoting the state’s renewable energy efforts. Dane County was named the Renewable Energy Pioneer of the Year in 2021. Beyond the Madison area, Wisconsinites like Nelson are advancing clean energy statewide. With initial construction set to begin in 2024 and a completion goal of December 2026, the High Noon Solar Project in Columbia County in south-central Wisconsin is one of the largest solar projects to be approved in state history according to Cooper Johnson, the renewable energy director at Invenergy.

Nelson’s choice to commit to the High Noon Solar Project didn’t come easy, however. While the utility-scale project faced pushback within his community, Nelson has emerged as a central figure in the effort to fuse farming and solar together — all while fighting for his family, his farm and the future.

Farming’s decline

Today the number of family farms nationwide continues to decrease. In the past two decades, the U.S. has lost 11 million acres of farmland, mainly due to development and increasing land rates, creating challenging circumstances for farmers to buy and rent additional acreage. The average price of agricultural land as of late 2022 was $5,551 per acre — a 23.5% increase from 2020.

Young people aren’t easing the situation either. The next generation of Wisconsin farmers are leaving rural communities and opting for other jobs in our state. The average Wisconsin farmer is now 58 years old.

At 58 himself, Nelson faced a similar dilemma: Two kids interested in opportunities outside of farming with semi-retirement for him and his brother Scott fast approaching.

Instead of sitting on the sidelines, Nelson decided to act. To him, solar is a path forward.

“It’s a new way of farming to assist farms and make them more stable,” Nelson says. “For us, and for many farms involved with our solar project, it’s a way to keep family farms in the family.”

Solar skeptics

Nelson wasn’t all in from the get-go — at first, he was skeptical.

When Invenergy came to Nelson about the High Noon Solar Project, he asked some important questions: How would solar affect the land, his income and the future of their farm? Discussions with Invenergy gave him the answers to debunk some common misconceptions.

While many people believe solar only produces energy when the sun is shining, solar energy can be leveraged in virtually any condition, tending to perform best in sunny, cold climates such as Wisconsin. This takes a majority of weather’s unpredictability out of farming, allowing farmers like Nelson to count on the sun’s rays as a reliable source of income.

Johnson says the company often receives questions about solar panels altering the topography, too. Concerns surrounding the sight, height and sound of solar panels prevail in every community, but Johnson says, “Solar is a good, quiet neighbor.”

Vegetative buffers and agricultural fences can also be put in to make solar farms less visible. These solutions gave Nelson what he needed to commit. Yet Nelson acknowledges the project faced pushback within the community, where locals feared a loss of tax revenue and voiced concerns about land preservation.

Nevertheless, the Wisconsin Public Service Commission approved the High Noon Solar Project in May with a 3-0 vote. Once completed, the project will provide enough clean energy for 58,000 typical homes, create more than 600 construction jobs in the wake of the county’s coal plant shutting down in 2026, and invest $239 million in tax revenues, payments to landowners and benefits to workers, according to Johnson.

A family’s choice

Including Nelson, 30 landowners in the communities of Leeds, Lowville, Hampton and Arlington are currently leasing portions of their property for the utility-scale project, with more predicted to sign on.

Approximately 500 acres of the Nelson’s land has been proposed to Invenergy which will be leased on a flat rate per acre. By doing so, Nelson believes solar will provide both his family and the farm stability.

“People always fight change,” Nelson says. “But this is our choice; this works for our family.”

Even former generations of Nelsons are on board with the change. Nelson’s mom, Norma Nelson, has watched the farm evolve from dairy to beef cattle to grain and now solar.

“Everything seems to be being pulled in that direction,” she says. “We want clean energy.”

Nelson’s dad, Wayne Nelson, agreed, putting it more simply: “I don’t have a problem with it.”

Through the years

From dairy to beef cattle to grain, the Nelson Family Farm has evolved many times since 1894. Now the family is beginning its next transition — to solar. While the High Noon Solar Project won’t begin construction until 2024, Norma Nelson reflects on how the farm and the Nelson family has changed over the years.

1957

1967

1980s

1990s

2000s

Today

Farming during a climate crisis

But beyond their immediate family’s choice, Larry Nelson sees solar as the path forward for farmers adjusting to the effects of climate change.

Globally in 2023, the BBC pointed to climate change causing record temperatures, rapid ice melts and extreme weather. Wisconsin has faced a “weather whiplash” this year, according to Wisconsin State Climatologist Steve Vavrus, as the state has alternated between the wettest years on record during the 2010s and experienced severe droughts in 2012 and 2023. In this year alone, there has been an extreme shift with the wettest start to a calendar year on record from January to April, followed by one of the driest periods on record from May to August.

To reach the state’s goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, Vavrus says we must both mitigate and adapt to climate change in unprecedented ways. One way to do so is by switching from fossil fuels and embracing renewable energy sources like bioenergy, geothermal energy, hydropower, marine energy, wind energy and solar power.

While the swaps will ultimately reduce carbon emissions, Vavrus says “a change of that scale can’t be seamless.”

Transitioning to something new like solar within a farming community can lead to a lot of finger-pointing. For those who are resistant to climate improvements, politicians and farmers often become targeted scapegoats. Nevertheless, Vavrus views Nelson and the farming community as positive cultivators moving the state in a greener direction.

“Farmers are a big part of the solution of the land … both in terms of reducing carbon emissions in the first place, and improving land management practices that benefit them and the rest of us,” Vavrus says.

Pioneers in farming

When the changes to our climate can feel catastrophic, farmers like Nelson who are prioritizing our planet can bring us hope.

According to the International Energy Agency, renewable energy sources are helping the planet avoid climate disaster. Solar and wind power continue to be the biggest drivers in reducing climate emissions, making their expansion crucial.

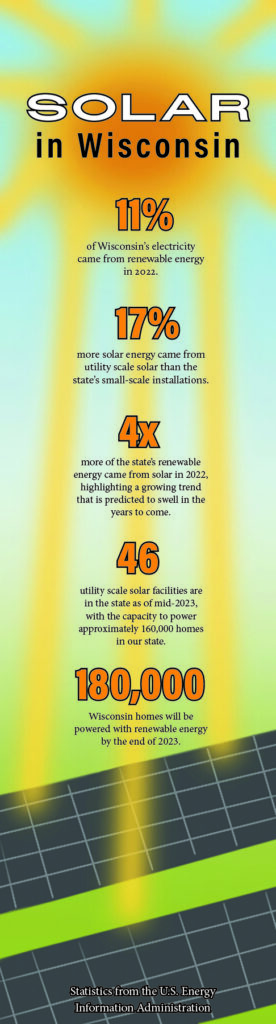

In Wisconsin alone, Invenergy has two renewable energy projects in operation, four in construction and two contracted, with three of them solar focused. These projects will provide Wisconsinites with more than 1,000 jobs and add $4 million in local taxes.

Projects like these would not be possible without support from the community. Throughout the entirety of the High Noon Solar Project, Nelson has remained an advocate and business partner, according to Johnson.

“It’s hard being a farmer, and I’ve learned a lot from Larry specifically about what’s happening locally in Columbia County,” Johnson says.

Challenges aside, Nelson sees solar as the future of farming. By educating his community, debunking misconceptions, introducing other farmers to Invenergy and pitching the prospects of solar, Nelson has introduced Columbia County to the next generation of farming.

“We are pioneers in farming now, in making this transition,” Nelson says. “It’s a golden opportunity for a farmer.”

When looking back on his family’s history of adaptation, Nelson sees solar as something greater than himself. On an external level, converting from grain farming to solar reduces carbon emissions, which will contribute to the globe’s net zero goal by 2050.

On a personal level, the change allows Nelson to keep the farm in the family for future generations and ease him into semi-retirement come 2026. This new chapter of the family farm considers not only the Nelson family’s legacy, but also the industry’s path moving forward — a path where Nelson says, “Solar is here to stay.”