In a softly lit studio, filled with the hum of old recordings and trinkets of the past, Norman Gilliland speaks into the microphone, bringing a familiar voice that’s told decades of stories to Wisconsin Public Radio listeners.

Since 1977, he’s been on air nearly every weekday, acting as a consistent voice connecting listeners to Wisconsin’s best and brightest musicians and scholars amid an ever-changing media landscape.

Gilliland is the host of “Midday Classics,” a classical music broadcast that features musicians, discussion about their work, upcoming shows and even live performances. Gilliland is also one of the hosts of “A Chapter A Day,” the nation’s third-longest running broadcast, during which he reads a chapter of a book for a half hour each weekday.

This summer, Gilliland’s mission to provide Wisconsin narratives and music grew far more difficult. In July, Congress approved a Trump administration plan rescinding $1.1 billion in federal funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting — ending all federal support for NPR, PBS and their affiliate stations.

The previously allocated funds were meant to support the Corporation for Public Broadcasting for the next two years, and without them, public media, including WPR, struggles to serve its communities.

Despite this sizable uncertainty, Gilliland remains steadfast in his mission to uplift and amplify Wisconsin voices and artists through his guiding broadcast philosophy: “live, local and interactive.”

“Live” means being on air in real time — sometimes 12 or 13 hours a day — connecting directly with Wisconsin listeners. “Local” means celebrating the state’s vibrant music scene, whether that be a concert hall in Madison or a community recital in Fond du Lac. And “interactive” means conversation: Each day, Gilliland poses a quiz question to his audience to make every broadcast a shared experience.

That hands-on style has made him one of Wisconsin Public Radio’s most trusted voices.

“It’s real people making real art, in real time… that’s what broadcasting really should be,” Gilliland says. “One real person talking to another.”

Building Community Through Music

Gilliland’s programs serve as a vital stage for the Wisconsin music community. His strong partnership with Madison Symphony Orchestra highlights both young, budding artists to legendary musicians.

“Midday Classics” gives Wisconsin musicians a platform, helping them gain visibility and confidence.

Each year, Gilliland hosts the finalists of the symphony’s annual Bolz Young Artist Competition, a highly regarded statewide competition in which Wisconsin’s young musicians compete for scholarships and the opportunity to perform as soloists for the orchestra. The impact of radio exposure for these young artists is “a catalyst” for their growth, says Peter Rodgers, Madison Symphony Orchestra director of marketing.

“He really cares about the future of classical music,” Rodgers says. “That’s one of the reasons that he’s so passionate about bringing these things to life, and he’s in a unique position to be able to do that with his position as a radio host that’s quite renowned within Madison.”

In 2015, Gilliland hosted the competition’s first-place winner, violinist Julian Rhee, who was a freshman in high school at the time. Rhee played a range of classics for the listeners of “Midday Classics” and appeared on the show three more times during his time at Madison Symphony Orchestra.

Nearly a decade later, Rhee rose to international prominence following his prize-winning performances at two of the most prestigious violin competitions in the world — a testament to the community impact of public radio for young artists.

Rodgers agrees, saying this is just one of many examples that illustrate Gilliland’s commitment to community and using his platform to elevate these emerging artists.

Challenges Amid Federal Cuts

At Wisconsin Public Radio, federal funding cuts meant the cancellation of four shows, including Gilliland’s “University of The Air,” a show that he co-hosted with UW–Madison English professor Emily Auerbach. The loss was deeply felt, not only by staff but by listeners statewide who relied on the program’s enlightening discussion of music, arts, literature, science, theater, education and history.

The uncertainty is sizable and imminent for many working in public media. With public funding gone, stations across the country have been forced to lay off employees, cancel broadcasts or even shutter completely.

While Gilliland’s own future now is as fragile as any time in his career, his major concerns lie with the future of smaller, rural stations in isolated places where radio and public media are the cornerstone of the community and its inhabitants.

“You’ll see little stations in Alaska that are, in some ways, even more important than those of us [Wisconsin Public Radio] who are bigger,” Gilliland says. “Those are the only source for the audiences up there in isolated places. That’s where you’re going to see the change.”

As the future of public media faces imminent threats, Gilliland reminds us that even if the landscape changes, its purpose does not.

“You go where they are, with the technology and also with personal development,” says Gilliland.

WPR’s Evolution and Resilience

As one of the oldest radio stations in the nation, Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHA is no stranger to adapting in the face of adversity.

Founded in 1917 by UW–Madison professors Earle Terry and William Bennett, Wisconsin Public Radio began as a tool to make life better for farmers by broadcasting weather forecasts and crop prices. The free weather forecast was the first of its kind — and revolutionary for Wisconsin farmers. With access to data on crop prices, it evened the economic playing field, putting all farmers in a better position to profit in an open market. With the free and valuable information at their disposal, farmers had the resources to make their own decisions and have more “power of their destiny.”

Public radio was invented at UW–Madison, but the big breakthrough wasn’t the radio technology, according to Jeffrey Potter, Wisconsin Public Radio’s marketing and communications director.

“We were the first ones to really say, let’s make it educational. Let’s use the airways to make people’s lives better.” Potter says.

While the audience and listening habits have changed, the station mission to use technology to make lives better across the state has not. In the past century, Wisconsin Public Radio has expanded its mission across news, culture and music to uplift and amplify Wisconsin narratives and voices.

“We were the first ones to really say, let’s make it educational. Let’s use the airways to make people’s lives better.”

“We’ll use whatever platform we can use to serve the people of Wisconsin,” Potter says. “If we want to serve people in Wisconsin, we need to reach them where they are.”

In May 2024, Wisconsin Public Radio restructured its statewide broadcasts into WPR News and WPR Music to help its listeners access channels more effectively, including the expansion of its locally hosted music schedule seven days a week.

The changes were aimed at addressing new trends in listening habits, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. With listeners forced to stay home, listening habits shifted as commutes were shorter or earlier in the day.

These challenges weren’t a roadblock for Wisconsin Public Radio, but an opportunity to find new ways to reach new audiences.

According to Sarah Ashworth, director of Wisconsin Public Radio, adaptation is essential.

“We have to be ready to continually evolve as a public media service, and we have to go along with our audience,” Ashworth says.

The decision to realign the network made Wisconsin Public Radio Music on 90.7 FM the first full-time classical music station in Milwaukee since 2007.

To both Ashworth and Gilliland, it was clear that there was a “real hunger” for classical music in Milwaukee.

Gilliland hopes to continue serving his audiences and their interests by providing more live performances and building partnerships with local theatre groups.

Amid political and technological change, one thing remains steady — Gilliland’s commitment to community and connection through public radio. After nearly four decades behind the microphone, he remains guided by the same principle that inspired WPR’s founders: using sound to bring people together.

Regardless of Wisconsin Public Radio’s next chapter, Gilliland continues to offer what he always has — a thoughtful voice, a love for music, and a sense of curiosity that engages his listeners to connect with Wisconsin stories and music.

the new generation of radio

Radio has long played an important role in public media, acting as an accessible vehicle of music and news for Wisconsin residents since its beginnings. Founded in 1917 by University of Wisconsin professors Earle Terry and William Bennett, Wisconsin Public Radio began as a tool to make life better for farmers by broadcasting weather forecasts and crop prices. But now, a century later, the landscape and the listeners have shifted, so the question remains — how is radio evolving while staying true to its mission? On this Curb podcast, Maggie Spinney and Cameron Hagen reflect on their experiences with radio and what kind of future they imagine for public media and radio.

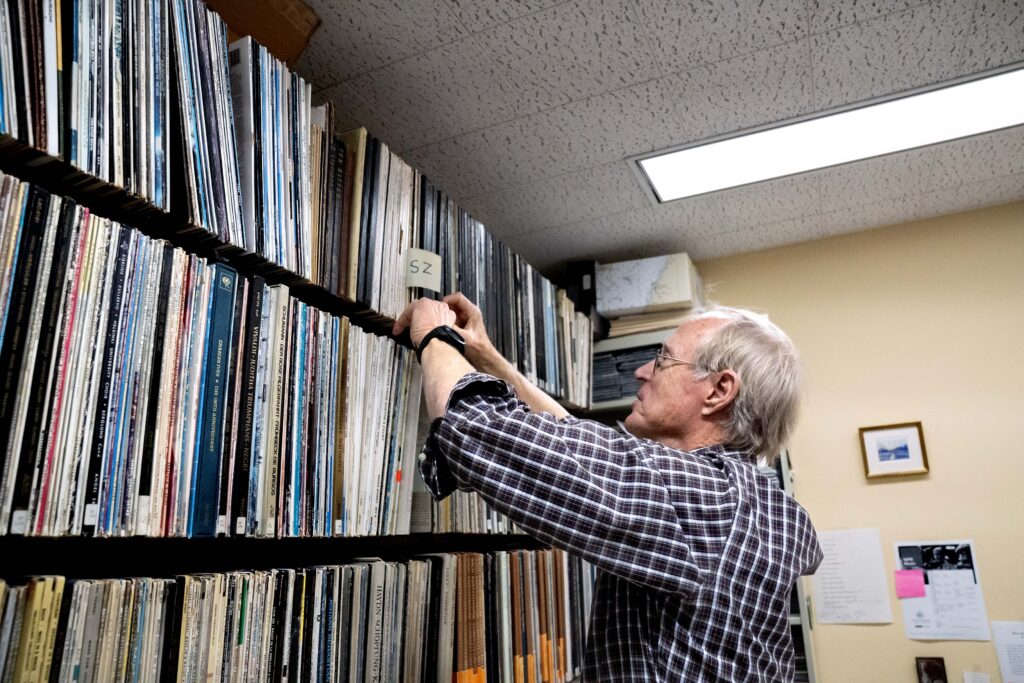

Feature photo: NPR’s Norman Gilliland has kept listeners company on air nearly every weekday since 1977. Photo by Maggie Spinney