Take a drive northward on Wisconsin’s Highway 13, and you will come upon something unusual.

Phillips, a small city in the Northwoods, is home to the Wisconsin Concrete Park, a wonder of the rural Midwest. Its 237 concrete sculptures honoring Native Americans, animals, and local myths and legends, all sparkling with broken beer bottle embellishments, represent the unbounded creativity — and frustrations — of Fred Smith, the artist who created them in the latter part of his life.

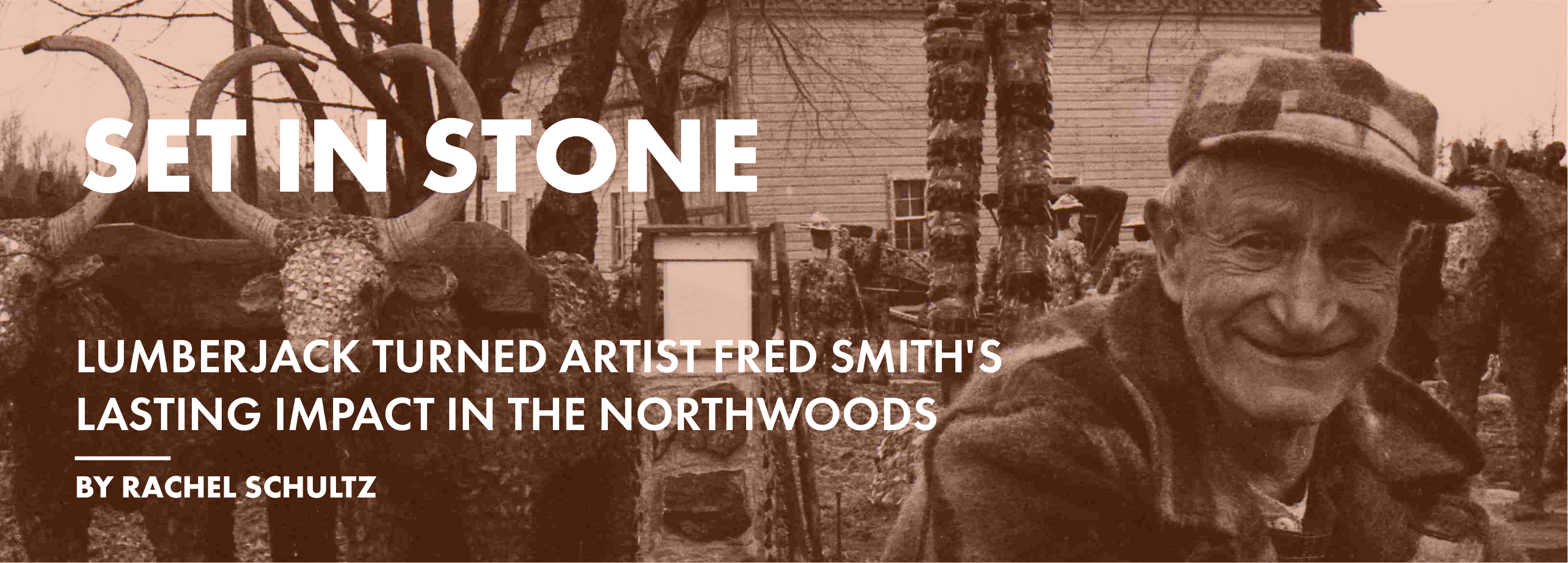

Smith was somewhat of a marvel. Working as a lumberjack in the Northwoods of Wisconsin since the age of 12, he was familiar with the dangerous and demanding yet respectable realities of the lumber industry. After retiring due to arthritis around 1948, he began creating larger-than-life sculptures and used his home and the land around him as inspiration and material for bringing these visions to life.

“He doesn’t even know why he did it,” says Ann Grzywnowicz, operations manager of the Wisconsin Concrete Park. “It was just in him.”

These creations emerged from his love of working with his hands and using the environment as inspiration, fueling his determination and unparalleled work ethic. Smith’s passion for art created opposition from his community, family and friends as they found it to be a strange waste of time and money. Instead of getting discouraged by these challenges, he found a way to persevere, learn the land, dumpster dive for materials and befriend the few creatives in town.

The fleeting nature of his past in hard labor pushed him to manufacture something more long-lasting — art. He unlocked his creative passion and crafted a legacy that would serve as an influence for artists in Wisconsin and beyond. What Smith provided to his community physically has manifested into a meaningful amalgamation of inspiration and purpose.

Smith challenged the norms of traditional gallery models and utilized sustainability, working off the land his creations would inhabit. Sculpture material was difficult for him to obtain, so he used what he had learned in his past, combining the materials of his lumber experience with the visions of his artistry. That makeshift strategy brought his art to life by connecting his lifestyle with innovation.

Now, years after his death, his legacy lives on through the appreciation of artists from all over. This place is no longer an eyesore or a waste of money but an expression of sustainable living and creating.

Lumberjack Fred

Smith was born to German immigrant parents in 1886 in the north central Wisconsin town of Ogema. His early life consisted of making work off the land in lumber camps. As a boy in his early teens, Smith had a dangerous existence. Lumberjacks in Wisconsin were at the mercy of the land and their machinery, never knowing when a sharp edge could scrape skin or a falling tree could miss them by a centimeter. Starting in the lumber industry at a young age and lacking a formal education, he was illiterate but never saw this as a hindrance.

Smith worked with horses to cut and move pine trees from one place to another only to receive a mere 99 cents a day as his starting wage — equivalent to about $36 today. In a grainy black and white photo, an elderly Smith sports a plaid flannel with a smile from cheek to cheek, proudly posing next to his work.

In 1903, he began to homestead 120 acres of land where he raised his five children and supported his wife, Alta. During this time, Smith began growing ginseng to sell in New York markets and using his land to raise Christmas trees. The property he had held enough space to construct a house, a rock garden and a rock garden tavern — the latter which he crafted with assistance from John and Albert Raskie.

“Fred was rooted in a life way that was hard, dangerous, respectable and available,” says Lisa Stone, co-author of “The art of Fred Smith: The Wisconsin Concrete Park, a brief history and self-guided tour.”

Isolation in the Northwoods

The secluded environment of Price County is made for logging, not for people.

The communities in this area are supported by labor workers and farmers, and they have a type of magical solitude that is appreciated by living in the area for quite some time or visiting for a weekend.

Although Smith’s severe arthritis may have caused him to leave the lumber camps, he worked through the pain, driven by his love for crafting with his hands. Smith’s 15-year project took over his life and left him little time for his wife, his children or his community. The unwieldy sculptures began to jeopardize his image in the area, where physical labor was king. Many in the community had a negative view of Smith’s artistic endeavors in his lifetime and likely for a while after. Even his immediate family resented his absence and felt embarrassed about the attention the sculptures brought to the family’s home landscape. After his death, they even called for the removal and destruction of the park.

“People just thought it was just a tremendous waste of money, because he’s spending all this money to make what didn’t look like art to them,” Stone says.

Smith suffered a stroke in 1964, which left him in a rest home and unable to work at the park.

“People say that even when he was in the nursing home, he would be having ideas of things that he wished he could continue to create,” Grzywnowicz says.

Smith’s boundless creativity would be cut short when he passed away on Feb. 21, 1976, at the age of 89. However, the Wisconsin Concrete Park is still standing today due to the Kohler Foundation acquiring the park shortly after Smith’s death with the help of Price County and the Friends of Fred Smith, who work to preserve this space.

Discovering Phillips, Wisconsin

Living in Price County, Grzywnowicz, the park’s operations manager, is witness to the constant preservation of the statues and the inner workings of the land that keep Smith’s statues standing.

“I would drive through Phillips a lot and see this place on the side of the road and was like, ‘What the heck is that? That is bizarre,’” Grzywnowicz says, reflecting on her journeys from Oshkosh to Hayward for family vacations.

Her work consists of overseeing the former tavern, which is now a community space for bridal showers, graduation parties and other events, along with assisting with the Airbnb rental property in Smith’s old home. The conversion of these spaces has allowed the community to be more involved with the park, which was a hard-fought battle.

“Some of the members of the local community are very unaware of how special the concrete park is,” she says.

Typically, it is hard to get the rest of the world to recognize a small, outsider artist, but here the opposite occurs.

“Most of the people in town would say they have never been there,” Stone says. “You know, it’s just the classic thing that you’ve never gone to — the thing that’s right in your backyard.”

Grzywnowicz is hoping to boost community involvement, knowing how much Smith enjoyed visitors.

“He especially loved artists who got it. They’d spend all the time in the world walking, listening to him carefully and asking insightful questions artist to artist,” Stone says.

The art of preserving concrete

Keeping a park alive isn’t easy, and there is no blueprint. While Smith was incredibly inventive, he was still working off what the land and his community provided him, whether that be the leftover scraps of wood or broken beer bottles.

Unfortunately, this created obstacles down the line.

“There was a huge storm that came through that was actually a blessing in disguise, because the statues fell and came apart, and the preservationists … were able to identify compromises in the frames,” Grzywnowicz says.

The group of dedicated individuals who work on preserving the beauty of these statues patch up the holes in the concrete caused by the long Wisconsin winters, reattach the fallen pieces of broken glass and mirrors that adorn the sculptures, and fill in cracks with special caulk.

The Kohler Foundation has also played a large part in keeping the memory of Smith alive. Its purchase of the Wisconsin Concrete Park in 1976 allowed for Smith’s work to continue living in the Northwoods.

“[Fred Smith] existed completely outside of any kind of academic framework,” says Fred Stonehouse, associate art professor at UW–Madison, about outsider artists like Smith. “He’s the person who made artwork, specifically sculpture, and like many outsiders, out of the things he had at hand and the things he understood.”

Smith fits the bill as he lacked formal education of any kind. His creative impulse can be seen as a mystery, but preserving his story allows his impact to thrive and influence other artists — outsider or not.

“He worked entirely through his own self-generated vision,” Stonehouse says.

Sustaining the Smith legacy and impact

While there was no telling at the time whether this vision would last, Smith’s ideas proved to sustain throughout the years and push past any boundaries.

“I think it is a very human practice that’s been going on for a really long time to use what we have in our hands and transform it into something magical,” says Marianne Fairbanks, associate professor of design studies at UW–Madison.

Reusing materials he found in dumpsters and the side of the road is impactful as he transformed the ordinary to become extraordinary. Smith represented the communities he interacted with, such as the Anishinaabe people, lumberjacks, or horses and other animals.

The appreciation of the groups around him led to endless ideas for his art, which only halted when he took his last breaths.

“While Fred was alive and doing his work, he was driven by his own personal motivation. It wasn’t like he was trying to make a lot of money or get accolades or anything,” Grzywnowicz says. “It’s amazing how many people have been inspired by his work.”