It was the Fourth of July weekend at Devil’s Lake, one of the busiest of the year.

Seth Taft, a local Baraboo resident, arrived with his windows rolled down, bracing himself to wait in a long line of cars entering the park. Laughter from children floated across the lake — normally a sound that would bring him joy — but today, it felt heavier.

Along with being a longtime visitor of the parks, Taft serves as the executive director for Friends of Wisconsin State Parks, the largest advocacy group in Wisconsin for state parks. For him, and for the millions of Wisconsinites who love the outdoors, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The state of Wisconsin’s biennial budget had just taken effect that morning, July 3, 2025, dealing a heavy blow to the parks.

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the Wisconsin State Park System — one of the oldest in the nation. But as it reaches this milestone, a sobering question looms: Will these parks still be here 125 years from now?

Despite being beloved by millions, Wisconsin’s state parks face serious challenges. The 2025 to 2027 state budget slashed funding for maintenance, staffing and improvements — leaving trails, facilities and programs at grave risk. Most visitors have little awareness of these hardships, enjoying the parks without knowing just how much work and money is needed for them to survive. Last year alone, more than 20 million people visited Wisconsin’s 50 state parks, a high that reflects growing demand, even as resources decline.

Although the state Department of Natural Resources still receives general purpose revenue — taxpayer dollars that fund a portion of its overall operations — that support has steadily declined over the past three decades. The state park system, which falls under the department’s management, has fared even worse. Since 2015, it has operated as a fully self-funded system.

Today, admission passes, campsite reservations and trail stickers provide nearly all of the revenue that keeps the parks open, and the department’s limited state funding offers little relief.

Between 1995 and 1997, the agency received $334.3 million in general purpose revenue. In the 2021 to 2023 budget, that amount dropped to just $197.5 million — a 41% decrease before accounting for inflation. With fewer public dollars to rely on, both the department and the parks it manages are increasingly dependent on user fees and volunteer labor to fill the gaps.

The impact of this long-term disinvestment is visible across Wisconsin’s park system. With an estimated $1 billion backlog in overdue infrastructure improvements, trails erode faster each season, restrooms and bridges show their age, and many of the Civilian Conservation Corps-era buildings deteriorate. What funding remains goes not to preservation, but simply to maintaining basic operations.

Taft says the list of overdue maintenance projects grows longer each year, and with limited staff and resources, some parks may soon face impossible decisions.

“You’re going to see, likely, discussion of property shutting down, cutting of staff. They’re going to have to try to gauge what’s the necessity,” Taft says. “And, unfortunately, some that still aren’t deemed a necessity can’t be kept going.”

A business model under strain

Currently, the park system operates under what officials describe as a “business model” divided into two areas: operations and capital development. Operations, which cover daily functions like staffing and maintenance, take priority, while capital development projects are deferred — often indefinitely.

“I will say that our staff do an amazing job of doing more with less all the time, and they make it look effortless.”

But even operational budgets fall short of what’s needed to hire enough seasonal and permanent staff or to pay them competitive wages.

“We continue to make reductions to our supply budget, and that’s the things that fund the fuel and the cleaning supplies and the equipment and all the different things that we need to operate these properties,” says Melissa Vanlanduyt, the recreation partnership section chief for the state Department of Natural Resources who oversees external relations for the state parks. “We continue to reduce our supply budget in order to fund as many of our seasonal staff and permanent staff as we possibly can.”

Vanlanduyt partners with organizations such as Friends of Wisconsin State Parks to support and promote advocacy and education goals across the park system.

One of the greatest challenges, she says, is simply getting more people engaged in the conversation.

“I will say that our staff do an amazing job of doing more with less all the time, and they make it look effortless,” Vanlanduyt says. “I think that that’s been a blessing for us and a curse, because I think that the public doesn’t always see it.”

Many visitors don’t even realize that Wisconsin’s state parks are now entirely self-funded. For Vanlanduyt and her team, part of the mission is to change that by helping people understand these parks depend on them not just as visitors, but as advocates.

For frequent visitors like Ava Glaser, a senior at UW–Madison, that gap in awareness is personal. She says she didn’t know that the parks had lost taxpayer funding until recently, and she worries that too few people understand how fragile the system has become.

“If people truly knew that their tax dollars weren’t going to parks, I think there would be a change,” Glaser says.

She believes that engaging young people is key to protecting Wisconsin’s parks for the future, and that simply reconnecting people with the outdoors can remind them how accessible nature really is.

“It doesn’t have to be big, and I think that’s the beautiful part about nature,” Glaser says. “It’s extremely inclusive, like you can be a part of it by just existing in yourself.”

That sense of belonging, she says, is what keeps her coming back.

Vanlanduyt credits much of the park system’s resilience to the various Friends of Wisconsin State Parks Groups. Aside from Taft, the organization’s board is entirely volunteer-run, yet its impact is enormous, contributing hundreds of thousands in project funding and tens of thousands of volunteer hours over the past five years. Their efforts have kept trails open, facilities functioning and programs alive.

But what began as community support has quietly evolved into a much deeper reliance, and Taft feels the weight of that reality every day.

After meeting Gov. Tony Evers, Taft recalls the governor emphasizing just how vital volunteer groups have become to the state’s parks — telling him that the Friends of Wisconsin State Parks are needed “now more than ever” to keep them running.

Evers’ words emphasize both the pride and the pressure carried by volunteers. The very people who step up for Wisconsin’s parks are now the ones holding the system together, reinforcing the need for more public education and awareness.

Parks powered by people

Despite the funding challenges, Wisconsin’s state parks have never been more popular. The attraction of these natural spaces extends beyond recreation, offering many visitors a sense of community and belonging.

For Wisconsinite Mark Arnold, the parks have shaped both his pastimes and his passions.

He grew up visiting Merrick State Park in western Wisconsin’s Buffalo County with his family every Sunday, and one afternoon, he watched an artist capture the landscape in watercolor. That moment sparked a lifelong love of painting — and of the parks themselves.

“I have finished, now, my 42nd summer of painting on site — landscape — so it certainly had an influence in that respect,” Arnold says.

Now living in Lodi, he often heads to nearby Devil’s Lake State Park, a spot he says feels worlds away from Madison’s bustle. He loves watching the park shift through the seasons, a tradition he shares with many who return to the same familiar trails year after year. It’s no surprise that Devil’s Lake is the most visited park, drawing roughly 2.4 million visitors annually — nearly as many as Glacier National Park, despite covering a fraction of its acreage.

Although the parks are in trouble, it’s people like Arnold who show how devoted Wisconsinites are to their parks. From staff who stretch every dollar to volunteers who give their weekends, the system continues to endure because people refuse to let it fail.

Vanlanduyt says that resilience comes from a shared passion for service and environmental stewardship.

“We have an incredible asset here in Wisconsin, and we have people who are so passionate about managing that resource, maintaining it, ensuring it’s here for not just another 25 years, but another 125 years or another 150 years or 200 years,” she says.

It’s that commitment that keeps her optimistic, even when the funding falls short.

For those who hike the bluffs, camp under the stars or simply find peace in the rustle of leaves, the value of Wisconsin’s state parks can’t be measured in dollars. The challenges ahead are real but so is the determination to protect these spaces. With enough awareness and enough voices willing to speak up, Vandylunt and Taft say it’s not too late to turn things around.

Wisconsin is still writing the future of its parks, one volunteer, one visitor and one small act of care at a time.

“We have a challenge, but we can do it great together. We can accomplish great things,” Taft says. “That’s what we’ve got to focus on.”

Arnold’s painting of the Ice Age Trail, which intersects with several state parks. Photo courtesy of Mark Arnold

One Tiny Park, Two Million Visitors

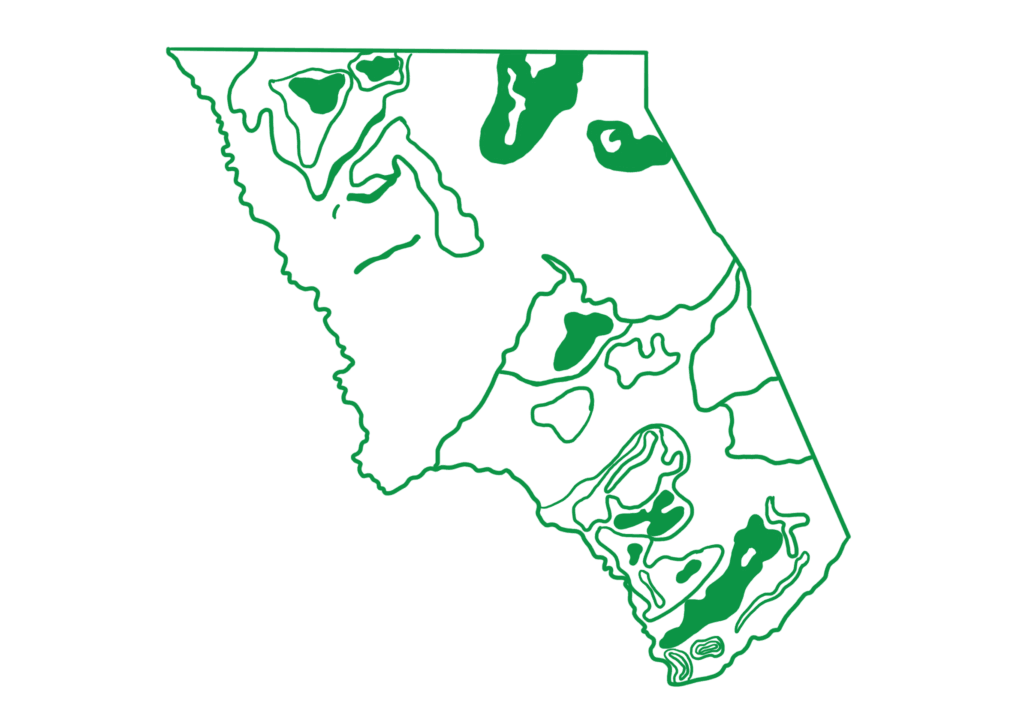

State parks are among Wisconsin’s most cherished spaces, providing places for families to gather, hikers to explore and communities to connect with nature. Yet many of these parks, despite their popularity, are showing signs of strain. Devil’s Lake State Park, one of Wisconsin’s most beloved and visited parks, welcomes roughly the same number of visitors each year as Glacier National Park — about 2.4 million — but it’s more than 100 times smaller in size. That means every acre of Devil’s Lake bears a far heavier load.

Without proper protection, Wisconsin’s state parks are in danger of overtourism, which threatens the state’s native biodiversity and limits the valuable experiences future generations will be able to share in.

Illustrations by Lenah Helmke

Feature photo: A rock climber takes on one of the trails at Devil’s Lake State Park. Photo by Lenah Helmke