Josh Herman grew up in Milwaukee as an ordinary kid in a Jewish household.

The synagogue he attended and the Jewish youth organization BBYO molded his Jewish identity. He went to rabbinical school after graduating from UW–Madison in 2009, then spent a couple of years living in Israel where he made Aliyah — a return to his spiritual homeland.

Herman was pulled back to his literal homeland three years later, coming to Milwaukee to serve the Jewish community that raised him. He now serves as the head of school at the Milwaukee Jewish Day School, which strives to create lifelong Jewish learners.

“I think we are big enough to have most of the major Jewish institutions that you need to have a vibrant Jewish community but small enough that everybody knows each other and half the people are related,” Herman says.

“It’s a real feeling of community.”

Two years ago, the Milwaukee Jewish community reinforced its mission of peace following the impact of the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks in Israel by Hamas. Today, numerous Jewish communities in the city are continuing to work toward a brighter future: one that keeps history alive, spreads Jewish values and promotes interfaith relationships to make life in Milwaukee better for every resident.

They’re working in a social environment where antisemitism is more pervasive and visible. Chad Alan Goldberg, a professor of sociology at UW–Madison, says sensitivity to the Holocaust is declining as the years go by.

“You can say that the way that the Holocaust entered public consciousness, the way that it was commemorated, really created a taboo around overt public expressions of antisemitism,” Goldberg says. “It didn’t mean that antisemitism went away or disappeared, but in terms of overt expressions, it really put a lid on it. But the further out we get from that catastrophic event, I think the harder it is for that taboo to remain strong and to remain intact.”

Cultivating a strong, resilient community

Jewish people started moving and settling into Milwaukee in the early 1840s. Because of the city’s religious tolerance and its variety of European communities — especially German — Milwaukee became an attractive place for Jewish people.

Although Jews now only make up less than 2% of Milwaukee’s population, according to a 2011 study by the Milwaukee Jewish Foundation, the vibrant city has long sought to cultivate a strong, resilient Jewish community.

Still, in 2024, the Milwaukee Jewish Federation reported an increase in antisemetic incidents in Wisconsin. Additionally, the federation says countless antisemitic incidents have gone unreported, likely due to fear of retribution.

The Holocaust Education Resource Center says teachers reported a noticeable increase in antisemitism in 2024, witnessing more Holocaust symbols and use of antisemitic tropes. The center says two especially concerning incidents happened in Wisconsin last year: one in which players from a Jewish school were taunted with “Hitler” chants during a basketball game, and another that involved students imitating the Heil Hitler salute during homecoming pictures.

The federation says no single solution exists to eradicate antisemitism, but sustained advocacy, education and interfaith relationships built by Jewish institutions in the community are critical to making progress against antisemitism.

Spreading Jewish values to improve Milwaukee

The Harry and Rose Samson Family Jewish Community Center in the Milwaukee suburb of Whitefish Bay is dedicated to spreading Jewish values in Milwaukee and throughout the state. Its main campus offers various physical and mental wellness programs as well as a preschool.

The center has a large percentage of members who do not identify as Jewish — a source of pride for the organization as it strives to help create a stronger community, says Julie Lookatch, the center’s chief communications officer.

The center also operates Bonim Farms, an adult workforce program for people with disabilities. Another program that the center supports is the Jewish Community Pantry, which has been operating for 50 years in Milwaukee’s Metcalfe Park and Amani neighborhoods.

“We do all these things for the community to serve the community, to live our values, but hopefully some of the side effects of that are that people who have encountered our organization … that they have a positive viewpoint and are hopefully less likely to be swayed by antisemitic tropes,” Lookatch says.

Stitching history

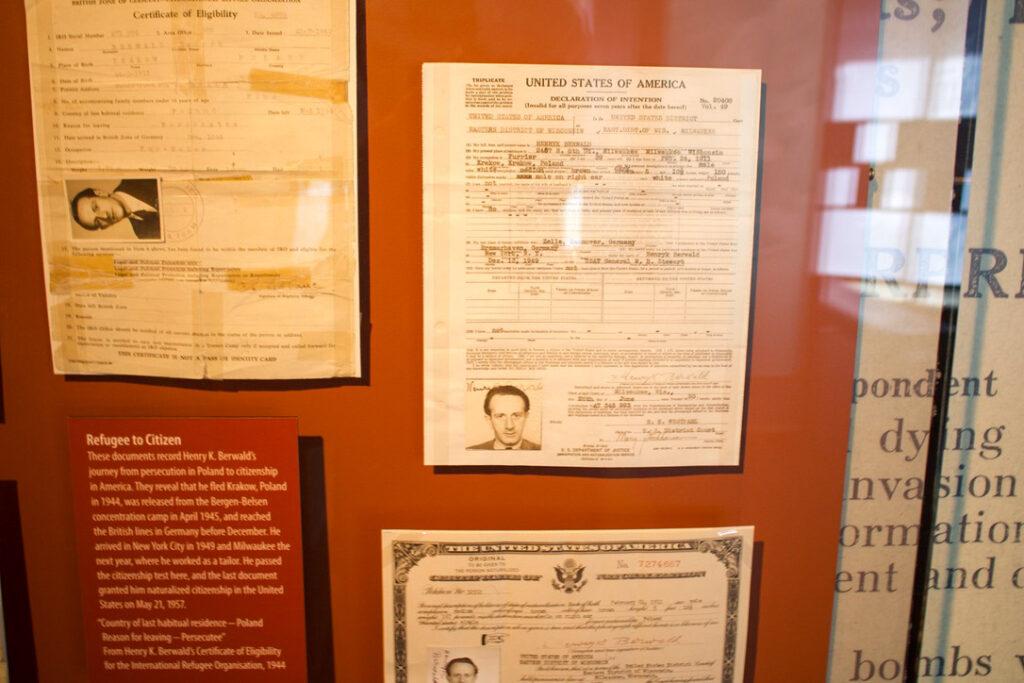

From European refugees to the many Wisconsin-born Jewish celebrities, Jewish Museum Milwaukee spotlights everyone’s stories to serve as an enduring reminder of the relationship between the city and its Jewish residents.

The museum, small in size but rich with content, strives to fight antisemitism by highlighting the ordinary and extraordinary Jewish stories that have made Milwaukee a better place. One of the most powerful exhibits focuses on the Holocaust and tells stories of Jews who sought refuge in Milwaukee or had family members in the city. Others tell stories of the laborers, entertainers and other professionals who called Milwaukee home.

One of the museum’s most prominent accomplishments was its 2014 exhibit “Stitching History from the Holocaust” that told the story of Hedvika and Paul Strnad, who were both killed during the Holocaust. The couple lived in Prague and were seeking refuge in Milwaukee, where Paul’s cousin Alvin lived. As the abuse of Jews by Nazi Germany worsened, they tried desperately to escape to Milwaukee. Due to immigration restrictions like the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, Jewish immigrants like the Strnads faced difficulty entering the United States. While Hedvika and Paul did not survive the Holocaust, the Jewish Museum Milwaukee was able to keep the couple’s legacy alive through the presentation of Hedvika’s dress designs. After the museum acquired Hedvika’s work, the exhibit traveled to eight states across the country.

The people who make the museum run are those who spend months doing docent training to lead tour groups through the space. Additionally, volunteers in the archives identify photos, process collections, clip articles from newspapers, and do critical outreach to family and community members to donate artifacts.

Beyond its exhibits, the museum has collected more than 15,000 photos and preserves Jewish life in Milwaukee through an oral history project, says archivist Jay Hyland.

Because Hyland isn’t Jewish, he wasn’t sure how well he would adapt when he started the job. However, Hyland says he has meshed with a Jewish community that welcomed him with open arms. Furthermore, Hyland says he’s impressed by the level of engagement the Milwaukee Jewish community demonstrates.

“Once there’s a cause, everyone just really rallies around it and is so dedicated to making something happen,” Hyland says. “And I think we found that in the museum as well, just how dedicated everyone is in terms of making the museum happen when it was first created.”

Teaching each other to bridge barriers

The Milwaukee Jewish Day School’s Repairing Together program, a partnership with three schools in Milwaukee — the Indian Community School, the Bruce-Guadalupe Community School and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School — fosters dialogue and a sense of community among all students.

Robert Ehrlich, the program’s coordinator, says Repairing Together is meant to bridge barriers between communities and create lifelong allies. As a result of the initiative, students at the school have completed various projects with their partner schools. Eighth graders at the Milwaukee Jewish Day School recently did a presentation about the Holocaust to their peers at the Indian Community School, who in turn gave a presentation about Indigenous boarding schools.

Additionally, elementary school students at the Milwaukee Jewish Day School participate in culture shares with their partners. This year, students at the Bruce Guadalupe School taught their peers about Day of the Dead, and both groups created Papel Picado, a traditional craft made for the holiday.

The school is also steadfast in ensuring that students feel proud of their Jewish heritage. The curriculum includes learning Hebrew so students can read classic texts. Students also learn about Jewish history and are exposed to modern Jewish and Israeli culture through music and Hebrew.

In a social climate where being Jewish is increasingly under attack, Herman says the work of the Milwaukee Jewish Day School has an even greater purpose, adding that the work his school is doing can prepare its students for a brighter future.

“They’re finding joy in learning and in singing these songs and learning these rituals and these traditions,” Herman says. “And that’s the hope, is that we are appropriately responding to the antisemitism and doing all that stuff that we have to do as a Jewish community and not losing sight of the fact that we have another generation to foster a love of our tradition.”

A Landmark Hiding in plain sight

One of the nation’s oldest synagogues is perched on a tiny plot of land in Madison’s James Madison Park

James Madison Park is 12 acres of land in Madison, made for playing sports, having a picnic or just relaxing. Anyone who walks through the park, however, might also see a small and really old-looking building. That is the Gates of Heaven synagogue, one of the most historic buildings still standing in Madison today. Its story goes well beyond being a synagogue, as it remains a useful building in Madison, even if it was built well over a century ago.

Wisconsin’s Famous Jews

Wisconsin’s small but mighty Jewish community has helped produce some of the biggest entertainers, sports figures and politicians in American history. Their stories started ordinarily, whether as native-born Wisconsinites or immigrants from other countries. However, some Jews from Wisconsin have made waves wherever they ended up.

Feature photo: The personal documents, like these identification cards, on display at Jewish Museum Milwaukee bring centuries of Jewish history to life. Photo by Dylan Goldman