Tasslyn Magnusson remembers being shocked when she started to see the pattern.

Magnusson, a lifelong lover of books who holds a master of fine arts degree in children’s literature, first spotted a spate of book ban attempts in her small town during 2021.

It was the same boom that led to a request to remove 444 books from the Elkhorn Area School District libraries in the opposite end of the state.

That’s when she combined her knowledge of research and love of reading to compile a list of all book ban challenges across the state, which she shares with her network of librarians and teachers.

Now, she’s known to some as Wisconsin’s “banned book queen,” and partners with PEN America to focus coverage on rural areas of the state. But it was her passion for the stories and librarians that led her down this rabbit hole.

“I really wanted to provide a resource for my friends and people I admired who were saying something’s going on and I don’t understand it,” she says. “You’re not crazy. It was really important for me to validate that what people were experiencing was true.”

Parents who say they’re concerned about books available to their kids have ignited a rush of book bans across our purple state in rural and urban areas. Most often they object to children’s literature featuring voices of people from underrepresented groups or deal with sensitive social issues. This politicization of children’s books and attempts of removal has left many to fight against what they believe is censorship, molding a community in the process.

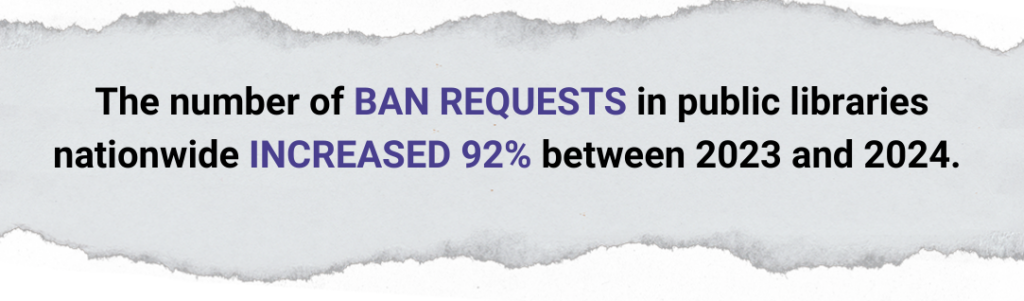

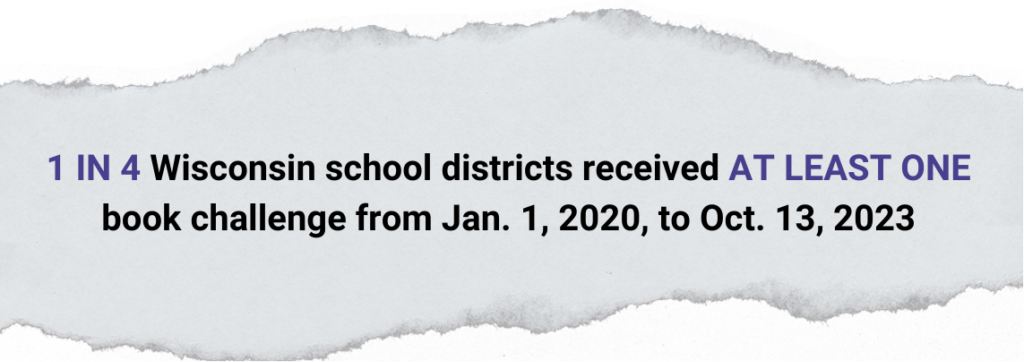

In the three years since Magnusson began recording book ban challenges, rates have skyrocketed across the state. More than 1 in 4 school districts have dealt with ban requests since 2020, according to PBS.

Wisconsin had the second-highest rate of requests in 2022, according to PEN America, an organization that works to protect free expression.

Dorothea Salo, a member of the teaching faculty in the Information School at UW–Madison, educates aspiring librarians how children’s literature book bans fall into the greater theme of fighting censorship.

“No, we are not letting you erase the record this way,” she says. “People get to hide what they did, hide what they were complicit in, and that’s not OK.”

Book bans are nothing new, although the most recent flare is the first to target children’s books, Magnusson notes.

“ They’re just incredible stories that will make you sad and happy and that are beautiful, and we should have access to them. “

In prior episodes, these bans were coming from a loud minority.

Now, 73% of all school district book ban requests in Wisconsin emerged from 11 “super requesters” who target 15 or more books at a time, according to Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit investigative news organization.

Large ban requests are most likely in districts with a chapter of Moms for Liberty, a conservative advocacy group in the U.S. focused on parental rights in education, or a similar group, Magnusson says.

The Elkhorn Area School District along the state’s southern edge saw the largest single request in the state of 444 books by one parent.

The objections spanned topics from bullying, police brutality, alcohol and drug use, alternate gender ideologies, aberrant sexual activity, mental health and more. Categories for removal are listed as “controversial commentary,” including cultural, historical, political, racial, religious and social.

“ You need both books that reflect yourself, that allow you to see other people and even allow you to experience what another person’s life could be like (…) And we do that through imagination. We build empathy through reading. “

Elkhorn Area School District Superintendent Jason Tadlock calls this incident a “shotgun” approach — where the parent scoured book ban websites and submitted requests based on what titles were considered problematic.

He believes the content of the requests was pulled from a website that catalogs lists of banned books, resulting in a 1,856-page total between the high school and middle school.

All books were eventually returned to the school, with some transferred up from the middle school to high school or requiring a parent’s signature to check out.

But this incident drastically changed how parents can request book removals in Elkhorn, Tadlock says. Parents now have to read the whole book they are challenging and argue that the majority of the book is completely unsuitable for students.

“I think the biggest exception that people took to the request to restrict or remove those books was one parent trying to dictate what other parents’ kids had accessed,” Tadlock says. “That was a very happy medium in the sense that any kid can still access all the materials they just needed their parent’s permission.”

To Tadlock, some censorship is necessary to maintain a healthy and safe learning environment for children, even if it has a negative connotation to many librarians. For example, not including pornography in libraries could technically be considered censorship, although few would argue for its relevance in a school setting, he says.

“Even the most progressive liberal librarian out there makes choices related to censorship, which they would hate to ever utilize that term,” he says. “Limiting the access to any material would be censorship. Even the most radical on one side of the issue would have to admit that at the end of the day, they’re making some decisions to not put certain books or materials in that library.”

In Oshkosh, public library director Darryl Eschete is aware that these ban requests can come from either side of the political spectrum. He recalls incidents of left-wing patrons calling for the removal of police instructional material or a “Berenstain Bears” book they claim reinforced gender roles in marriage.

Eschete, who has worked in libraries ever since he became a page in high school, has made it a point to remain neutral and objective in these book challenges. He calls librarians the “defense attorneys” for books.

As Wisconsin’s public defender of books, Magnusson is also driven by a love of stories.

Photo courtesy of Tasslyn Magnusson.

“There’s so many amazing stories to read that they’re taking out of libraries,” Magnusson says. “They’re just incredible stories that will make you sad and happy and that are beautiful, and we should have access to them.”

Many of the children’s books challenged across Wisconsin tell delicate stories about marginalized identities. Magnusson says that these stories are important not just for the reader to see themself in the story, but for observers to gain empathy through reading.

“You need both books that reflect yourself, that allow you to see other people and even allow you to experience what another person’s life could be like,” Magnusson says. “And we do that through imagination. We build empathy through reading.”

The politicization of children’s books has spread beyond the classroom and library walls. In Wisconsin and other states, lawmakers have introduced bills — with varying levels of success — to remove protections for libraries, define obscenity in books and strengthen parental control over library accounts.

One bill in Wisconsin sought to remove legal protections from librarians who distribute “obscene” materials in their libraries. It didn’t pass.

Photo by Lauren Aguila.

As a previous academic librarian, Salo is skeptical of these laws.

“The scariest thing that I am seeing right now is library closures and librarians being fired and laws being passed that allow the criminalization of library collection development, as in, a librarian could be sent to jail for purchasing a book about queer people,” she says. “That’s terrifying.”

Even without jurisdiction, thin lines of “obscenity” can impact funding across libraries and school districts, Magnusson says. She describes a “degradation of the public library,” where all controversial content may be labeled as unsafe.

Magnusson is preparing for children’s book challenges to continue.

“I think it’s going to get a little bit worse,” she says. Since diverse books are relatively new to the past 10 to 15 years, “it’s going to be harder to both get those books back and to continue to keep them.”

Salo is more optimistic, examining this rise of bans compared to previous historical examples coming from a small group, where the “energy kind of evaporates,” she says.

Those fighting book bans are all willing to stand up to censorship in their unique ways.

“In my career, I’ve never met a librarian who’s not willing to put their career on the line to defend the First Amendment or intellectual freedom, and I’m one of them,” Eschete says. “It’s a hill that I feel that librarians are called upon to die on if they have to.”

Book Bans

Book bans are not only on the rise across Wisconsin, but a movement to remove books from schools and libraries has swept across the country. Those tracking this trend say challenges to children’s books have escalated in recent years, often led by a small group of parents or community members. Wisconsin had the second-highest number of book bans and challenges in 2023, for a multitude of reasons. This data captures the spirit of those petitioning for bans and those on the front lines recording these challenges for future generations.

Sources: Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Watch, the American Library Association and PEN America

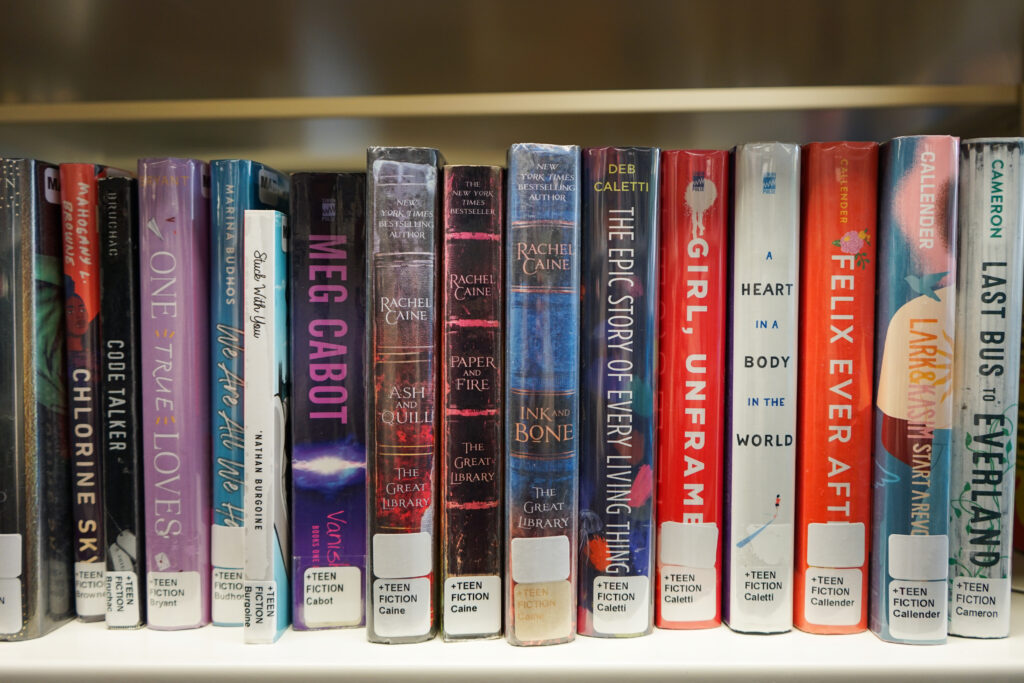

Cover page: Books lined up on a shelf. Photo by Lauren Aguila.

Tile Page: Books lined up on a shelf. Photo by Lauren Aguila.

Defending books, defying bans

Wisconsin ranks second-highest in book bans and challenges across the U.S. In both school and public libraries, children’s books are being increasingly targeted by groups across the political spectrum, but most commonly conservative voices. Book bans have become controversial for murky definitions of what is “obscene,” and blurring the line between protecting children and censorship. Bryna Goeking interviewed Oshkosh Public Library director Darryl Eschete about the effects of book bans on local libraries and society at large.

Published on Dec. 9, 2024