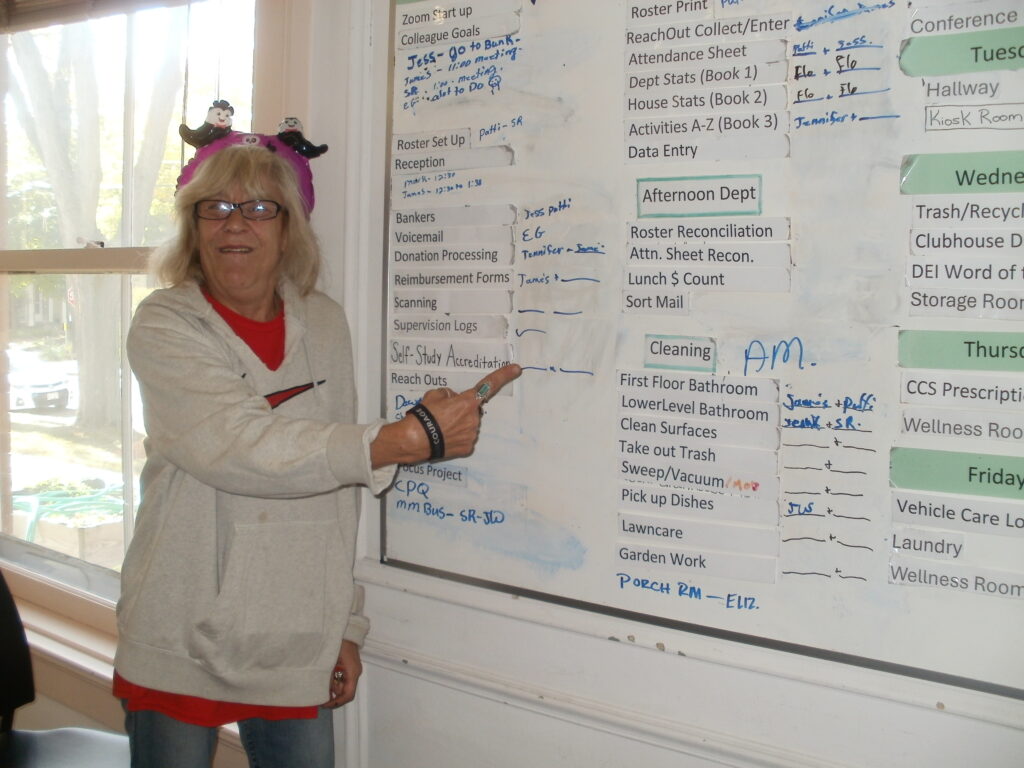

Jennifer Wunrow — the self-proclaimed “biggest mouth of the Yahara House,” — says the program saved her many times.

“I didn’t have no mom and dad to teach me. I didn’t have nobody to teach me but the streets of Madison, Wisconsin,” says Wunrow, who has been a member at the Yahara House for 27 years.

She spends Tuesday through Friday afternoon at the Yahara House, a historic mansion overlooking Lake Mendota, which has housed a work-based mental health recovery program since 1994.

When Wunrow found the Yahara House in 1997, she had no idea how it would change her life. The program gave her access to education, a stable routine and meaningful relationships. The Clubhouse even paid for Wunrow’s schooling, making it possible for her to get her certified nursing assistant license, which she would use for 15 years.

While Wisconsin only has four accredited clubhouses, the state’s neighbor, Michigan, is the gold standard for the clubhouse concept, with 40 locations and strong governmental support.

“ Recovery stories are the best way to change hearts and minds about stigma and correct assumptions and misperceptions about people with mental health challenges.”

Madison’s Clubhouse advocates — the Yahara House’s preferred term for staff — are hard at work fighting for increased funding and support for the program. They hope to catch up with states like Michigan so they can offer life-saving care to any Wisconsinite who needs it.

“We often hear that the Yahara house is the best-kept secret,” says Elizabeth Gonzalez, a clubhouse coordinator who has been at the Yahara House for seven years. “I don’t want that.”

A unique approach to mental health treatment

In 1994, Clubhouse International started on the steps of a library.

It was born out of the deinstitutionalization movement, which aimed to move “severely mentally ill” people out of large state institutions and then close those institutions, in the 1940s and 1950s, the group known as WANA — which stands for “We Are Not Alone” — was made up of people who were let out of institutions without any support system in the community.

The group met regularly at a library in New York City, and gradually became Clubhouse, Gonzalez says.

Now, there are more than 350 clubhouses in 32 countries, offering “hope and opportunities” to people with mental illness.

Clubhouse programs are recognized as evidence-based programs, says Yahara Clubhouse Director Brad Schlough. Uniquely positioned to “break down stigma,” Yahara has photos and names of members lining its walls.

“Recovery stories are the best way to change hearts and minds about stigma and correct assumptions and misperceptions about people with mental health challenges,” Schlough says.

To ensure that the program is best supporting members’ recovery, accredited clubhouses have to follow a set of 37 standards, which Gonzalez equates to a “bill of rights” that are reviewed by the worldwide clubhouse community every two years. The document includes standards about membership, relationships, employment and education.

Each location, including Yahara House, also has their own set of rules and regulations, which take a consensus to pass. And with somewhere between 100 and 150 active members, change is slow.

“ I was so sad and miserable living by myself,” Adams says. “I’m not so sad now because I have a family every day to come home to — this is a family here.”

“Consensus essentially means people might not love it, but they can live with it,” Gonzalez says. “A lot of our meetings and processes are slow and change is slow, but it also ensures that every voice has an opportunity to get heard and be taken seriously.”

Yahara House separates itself from other mental health services through what Gonzalez calls a “gymnasium” for people to practice their skills.

“A lot of what we would do in therapy — people that needed a venue to be able to practice what we were talking about,” Gonzalez says. “And it’s very difficult to figure out how to help people to do that. That’s kind of where the Yahara House comes in.”

Clubhouse stands apart from other behavioral settings, Gonzalez says, by giving members the agency to come when they want, and move freely around the house. Rather than focusing on clinical background, advocates spend time focusing on community and building relationships.

“I think [the goal] really is about creating community and reducing stigma around mental health and really having a place where everybody feels like they can belong,” Gonzalez says. “We believe medications, psychotherapy and group therapy — those things are really important — but people really don’t heal and recover in a vacuum.”

Gonzalez calls it “refreshing.”

“I have colleagues, I don’t have clients, so we are very much on an equal playing field,” Gonzalez says. “It’s a great program, and really, one of the joys of the job is watching people thrive.”

For Gonzalez and other Yahara House advocates and members, the main tenant of the clubhouse is that “work is recovery.” The house allows members to participate in transitional employment, a system where advocates learn positions at local businesses and members work shifts to earn money.

Gonzalez, for example, oversees a transitional employment program — called TEP — at Medical Health Pharmacy in Middleton, and other house advocates oversee programs at UW–Madison and Hyvee, among others.

“The only criteria for engaging in our TEP is the desire to work,” Gonzalez says. “We as staff learn those positions and get trained on them so that the employer then does not do any of the training.”

Clubhouse advocates gauge interest in a position, take members to see and shadow the job, where they will then work for about six to nine months with some onsite job coaching, before advocates slowly fade out and the member takes over the job.

But the biggest benefit to employers, Gonzalez says, is Yahara’s willingness to cover a shift if members are unable to show up — whether that be because of standard sickness or issues related to their mental illness, like sedation from medications.

“We guarantee that those shifts will be covered,” Gonzalez says.

Wunrow, who would “recommend Yahara House in a heartbeat,” calls the transitional employment plan a good opportunity to get in the workforce.

For Floryne Adams, who found Yahara House 12 years ago, says working in the house’s “Biz” department — tracking members, helping people with housing and washing donated clothes among other things — makes her feel good.

“They have completed my life from being down to uplifting my spirits to be around these beautiful people,” Adams says. “Everybody gets along.”

What it gives to members and staff

For members, Yahara House has become more than just a safe refuge from the harsh realities of the outside world. Much like its name suggests, it has become a home away from home.

“It gives me strength, hope,” Wunrow says. “It gives me the opportunity to get out of my bedroom and have a meaningful place to go for my mental health and relationships.”

Wunrow says she used to fall into deep states of depression due to mental health issues, which sometimes even resulted in hospitalization. Something changed the day she walked through the doors of the Yahara House.

“I’ve been out of the hospital since I started the house,” Wunrow says.

On community-oriented days, such as holidays, Yahara House aims to offer an accessible place for members to go.

“We are open every holiday for three hours,” Gonzalez says. “Everybody needs somewhere to be on a holiday.”

For Adams, who fondly describes her favorite memories as corresponding with different holiday celebrations, Halloween is a time for entertainment.

“Everybody gets a costume and then you can win ‘Best Costume,’” Adams says. “I love to get up there and dance. I love to sit here and sing, keep everybody’s spirits up.”

And with so many people gathering together at Yahara, Thanksgiving is a time for community, though Adams says “you got only so much time to eat.”

Adams, who had never tried Indian food before sitting down for a Christmas meal alongside her fellow members, calls the holiday a time for new traditions.

These relationships, fostered at Yahara House are critical to the retention of its members. For Adams, they are crucial.

“I was so sad and miserable living by myself,” Adams says. “I’m not so sad now because I have a family every day to come home to — this is a family here.”

The Yahara House works, so why can’t we get more in Wisconsin?

Despite the testimonials and evidence to prove the program’s effectiveness, clubhouse services have failed to grow in Wisconsin, largely due to the restrictions on their main funding source.

Medicaid, the federal-state health care program for low-income adults and children, funds the Yahara House. However, Medicaid doesn’t provide the program with enough money to expand their services, and what money they are given comes at the cost of mountains of paperwork.

Unlike Michigan, which requires documentation every 30 days, Wisconsin requires a “tremendous amount” of paperwork, making billing difficult.

“It’s maddening and it’s ridiculous,” Schlough says. “It’s forcing staff out of work.”

Gonzalez, too, feels the strain of this funding source, with her work being impeded by paperwork on the daily.

“Over time, we’ve been able to do less in the clubhouse because the staff are getting pulled to be sitting in front of our computers, typing recovery plans, assessments and progress notes,” Gonzalez says. “But at the same time, that’s what’s keeping our doors open.”

Yahara House is ultimately built upon relationships, she says. Because paperwork often takes away from the more rewarding daily tasks, turnover in staff is inevitable, affecting the stability of members’ environments.

To combat these complications, Gonzalez and the rest of the Yahara House staff have begun looking elsewhere for funding options that are less time consuming and restrictive.

“We’ve just been doing a ton of advocacy to try to see if we can get legislators on board to then sponsor bills that would write in codes and billing mechanisms that would just make it so much easier for us,” Gonzalez says.

In the last legislative session, lawmakers proposed a bill that would have awarded grants up to $500,000 a year toward clubhouses, but it didn’t receive a vote. State Rep. Francesca Hong (D-Madison) called the result “disappointing.”

Hong first visited Yahara House earlier this year for an open gallery night where she purchased a painting of the Pokémon character Charizard for her son. She recalls instantly feeling a sense of community and said she thinks Madison could “absolutely” benefit from another clubhouse location.

“There aren’t enough psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, social workers to be able to meet the need of mental health issues right now in the community,” Hong says. “It’s [Yahara House] both preventative and a safe space for folks in that community to be able to thrive in however way that they need to.”

But efforts continue, clubhouse advocates want to be able to serve every Wisconsinite who needs that safe space, because they’ve seen and heard how it can make a difference in members’ lives.

About a month ago, Gonzalez says she received a phone call from a woman who had been a member at the Yahara House 15 years earlier. The woman wanted to check in, see which of her friends were still at the house and reiterate that the Yahara House is the reason she is still alive.

She is just one of the thousands of Yahara House’s associate members — former members who no longer actively come in or receive case management, but will always be a part of the program.

“Once a member, always a member,” Gonzalez says.

Published on Dec. 9, 2024